ARTICLES

Reflections from Self Discovery

I recently had the privilege of watching Chris Williamson live in London as part of his ‘Self Discovery’ tour with my brother. For those of you who aren’t familiar with Chris’s work yet as the host of the Modern Wisdom podcast, I’m about to introduce you to a world of interesting insights from some of the worlds brightest and most interesting humans. He has hosted guests of the likes of David Goggins, Dr Jordan Peterson, Sam Harris, Dr Andrew Huberman and more recently Matthew McConaughey. On top of the podcast, he has also been running a series of live shows called ‘Self Discovery’.

The live show was a mix of thought-provoking stories, actionable advice, plenty of moments that made me rethink the way I approach personal growth and jokes that would’ve enraged a more 'humorously fragile’ audience — but in this room, they landed like a charm.

To say that his show and podcast more broadly has had an immense influence on how I think and approach life would be an understatement and I owe much of my personal development to the conversations that he’s had on Modern Wisdom. So in this article, I’m going to share some of the most impactful reflections I’ve had from the show.

External Doubt

Given that the Modern Wisdom audience—much like my own—is deeply invested in personal development and the journey from a flawed past self to an enlightened, disciplined, and successful future self, it's no surprise that self-doubt often emerges as a challenge along the way. This theme featured prominently in the show, as doubt and uncertainty are inevitable companions for anyone striving to grow and transform.

In fact, one of the most impactful points that Chris mentioned during the show was the misconception that in the journey towards success, the conviction of those who reach it rarely falters. They set their mind to this righteous goal and their self-belief pushes them towards success despite any hiccups along the way. In reality, this is rarely the case. It is easy for those who have achieved success to portray a sense of certainty in their journey, but in truth, the journey for most will be full of self-doubt, uncertainty, unpredictability and no guarantee of any real payoff in the end. It is life’s big gamble. And this is the reason why it becomes much easier to fall back to the comfort of the person you used to be and why so few people are able to maintain a positive change.

Those unwilling to endure the discomfort of this transcendence of growth will often attempt to thwart your own progression, damage your self-belief more so than you inflict on yourself and attempt to convince you that your journey of progress is a futile one. This is where Chris shared a quote from an unlikely place that resonated far more than it should have: “Your boo’s mean nothing, I’ve seen what makes you cheer” from… Rick Sanchez (yes, that Rick from Rick and Morty).

Reflecting on this, I think the key takeaway is to realise that those who are most critical or eager to instil doubt in others often do so because they themselves are unable or unwilling to pursue the same ambitions. And this doubt frequently stems from a place of jealousy or insecurity. So ask yourself: Why take advice on where to travel from someone who’s never left home?

The Lonely Chapter

The so-called lonely chapter is something that Chris discusses in many of his podcast episodes and it’s a concept that I think many on their path from who they are to who they want to become will experience. So let’s quickly define what it represents. As you move on your journey of growth, and begin developing new habits and skills that improve your character, you may notice old friends — whose habits, motivations, or goals no longer align with yours — begin to drift away. However, you have not yet developed your character sufficiently to find your new group of people. This creates a valley of loneliness and uncertainty in your personal evolution. This is the lonely chapter and it’s a common step in the journey of most successful people.

This is something that I’ve dealt with after moving away from home in pursuit of opportunities and a career as a spacecraft engineer. But one of the things that hit me hardest during the live show was when Chris revealed the revelation that you may have to (and many people do) go through the lonely chapter multiple times during your life as you continually grow and develop your character.

But it made me realise that ‘loneliness’ isn't a sign of failure or isolation, but rather a natural byproduct of personal evolution, where each new phase of growth requires letting go of old versions of yourself, only to rebuild stronger connections along the way.

Do the Thing

It’s often the simplest pieces of advice that resonate the most with us. And sometimes, we may already know the advice deep down, but it takes someone with a microphone on a stage in front of 3,000 people to say it for it to really land. For me, this was one of those times. I’ve got a pretty bad habit of overthinking decisions (particularly big or important ones). I will spend hours thinking about how to begin a task or what task I can do next to make the most progress. While this sounds good in theory, in reality I end up wasting hours on this mentally exhausting task of trying to strategise doing ‘the thing’. Why this is, I’m not too sure. Perhaps it’s a fear of making a mistake, of wasting time going down the wrong direction of doing the thing, or some deep rooted perfectionism that’s saying “if you don’t set off down the right path, then you won’t achieve perfection”. Well that may be the case, but as I try harder to live by the principle of pursuing progress, not perfection, I begin to push against this perfectionistic thought rabbit hole.

So what was the piece of advice that Chris said that resonated so deeply with me? To paraphrase, something like this:

Thinking about doing the thing is not doing the thing.

Making a to-do list for the thing is not doing the thing.

Telling yourself you’re going to do the thing is not doing the thing.

Telling others you’re going to do the thing is not doing the thing.

Waiting for the motivation to do the thing is not doing the thing.

Planning every step of the thing is not doing the thing.

Organising your workspace to do the thing is not doing the thing.

Going to the Self Discovery show is not doing the thing.

Reading articles on productivity is not doing the thing.

Actually doing the thing is doing the thing

It’s simple advice, but something that many people needed to hear. It’s great to stand at the base of a mountain imagining how amazing the view from the top is, but you’ll never see that view unless you take the first step.

Anxiety Cost

The final takeaway that I want to share in this article (although there’s plenty more that I could share) is something called the anxiety cost. Until I was introduced to this idea from the Modern Wisdom podcast, I struggled to put a name to this feeling I had most days. So what is the anxiety cost. Well suppose that you start the day with a list of things you have to do (these don’t necessarily need to be in the form of a to-do list - just tasks you have to accomplish during the day) and you leave them until later in the day to complete, then you will have to spend a longer portion of the day thinking or worrying about doing those things. This is the anxiety cost.

The solution? If instead you set a morning routine, you can then tackle some tasks early in the day without spending a significant amount of time ruminating on them. For example, let’s say that in a given day, you want to read 20 pages, meditate for 5 minutes, walk for 30 minutes, hit the gym and write for 1 hour (which I hope you agree are fairly reasonable tasks for a given day). Setting a morning routine where you wake up early, meditate for 5 minutes, head on a walk and spend time reading all before the day really begins, means that the only tasks remaining tasks to occupy your mind for the rest of the day are going to the gym and writing. And as a result, you’re far more likely to perform better at those important tasks without the worry of the other tasks which have already been completed.

The anxiety cost is the result of Parkinson’s law, which states that work expands to fill the time available for its completion. Completing tasks earlier not only breaks Parkinson’s law but reduces the anxiety cost you pay for those tasks. I’ll admit that it’s not necessarily always easy to do, but believe me, when you start your day by completing several tasks in the morning, the rest of the day will become some of the most productive time you’ll experience!

Final thoughts

As you can imagine, I found the Self Discovery show to be deeply insightful and it has inspired me to reflect deeply on my values, choices, and the direction of my personal growth. If you ever have the opportunity to attend one of Chris Williamson’s shows in the future, I would highly recommend it. It’s an experience that not only challenges your perspective but also inspires meaningful change.

Does stoicism actually help with grief?

Grief is a universal experience which will likely be experienced by everyone at some point in their lives. It is a natural emotional response to the loss of something that is often times irreplaceable and while this is often associated with the loss of a family member or friend, it can take many different forms from the end of a relationship, loss of a job, or another major life change. Grief is often a hard hitting emotion due to a combination of two factors:

We lose something irreplaceable and important to us

We experience grief significantly less frequently than other emotions (many people will experience grief just a handful of times yet it can have long lasting - even lifelong - impacts during their lives)

I recently have been dealing with grief following the passing of a close relative of mine, and in searching for comfort during these times of sadness, I realised that much of the wisdom within the works of the ancient Stoics could be directly applied to my situation and ease the discomfort of dealing with such a strange emotion. This article differs slightly from my others in that I’m not trying to suggest any real strategies in dealing with grief - I’m not a psychologist and definitely not qualified to offer concrete advice on dealing with grief. Rather, my goal with this article is to explore and share my experience in applying Stoic principles to the tragedy of death.

What does Stoicism teach about grief

In dealing with grief, people find comfort in a range of different ways. This could be family members, friends, therapists, religion and in their own philosophies. One such philosophy that has stood the test of time, yet often is misrepresented in the modern age is Stoicism which, at its heart, teaches that we should focus on what we can control and worry not about factors which we cannot. This dichotomy of control is pivotal in Stoicism: external events are beyond our control, but how we react to them is within our power. By cultivating an attitude of acceptance and rationality, Stoics aim to maintain inner peace regardless of external circumstances.

Anyone who is remotely tuned into the teachings of Stoicism will have read or heard the infamous phrase: “Memento Mori” which loosely translates to “Remember that you must die”. At first glance, this phrase seems like a morbid and grim concept to be teaching its readers who may very well be young, healthy and years away from death. But Memento Mori doesn’t serve the purpose of propagating the nihilistic morbidity of death, but rather to instil a sense of perspective, appreciation and purpose for the time that we do have alive. It’s phrases from Stoic literature like this that have helped so many to deal with grief. During my grieving process, I found that three facets of Stoicism were particularly useful.

1. Focus on the controllable

One of the foundational ideas of Stoicism is the distinction that forms between what is within our control and what is not. This is one of those principles which on the surface appears simple and trivial to implement but it requires a lot of thoughtful effort to fight back against the natural anxiety that can arise in unfamiliar situations. In the context of death, the fundamental Stoic principle is recognising that the fact that what has been lost or who has passed cannot be changed, and instead, we are able to control how we cope with death and how we react to it.

This is not to say that the recommendation is to not ‘grieve’ in the traditional manner and to supress all emotions, but rather to control your emotions in such a way so that you are still capable of supporting and comforting those around you who may not display the same level of control over their emotions. I’ve found this, not only to be a valuable skill in dealing with grief, but in life in general.

For me, I found that focusing on controlling thoughts and perceptions about the situation instead of ruminating on the loss to significantly help. Additionally, accepting that death is a natural process and embracing its inevitability can help mitigate the shock and pain associated with loss.

2. Find strength in virtue

The Stoic philosophy is rooted in four virtuous traits: Wisdom, courage, justice and temperance. Applying these four virtues in the context grief is a powerful way of dealing with the complex emotion. Let’s start with wisdom: Here we can use logic and reason to understand that grief, while painful and uncomfortable, is a natural response to loss.

Courage allows us to face grief head-on with bravery and gives us the ability to allow ourselves to feel the emotions that come with grief without letting them overwhelm us. Justice pushes us to honour the memory of the person lost by living in a way that reflects their positive qualities and contributions and in a way that would make them proud of the legacy that they left upon us. Finally, temperance: Practice self-control and balance the expressions of grief. Avoid excessive indulgence in hedonic escapism, aiming instead for a balanced approach to mourning, always pushing forward to a better version of yourself.

3. Reflect on the impermanence of life

As mentioned in the introduction, one of the most infamous phrases in Stoicism is Momento Mori (remember that you must die). Reflecting on this regularly may seem morbid, nihilistic or unnecessarily negative but I disagree. I found that the important factor in considering Momento Mori is how it is framed. Sure, it could evoke a sense of dread or worry, but if framed correctly it can instill a sense of perspective and appreciation for the time we have. I also find that regularly practicing displaying gratitude and reflecting on positive experiences and the lessons learned from them to be massively beneficial.

Finally, one thing that Stoicism also teaches is the interconnectedness of the natural world in a sort of proto-deterministic philosophy. To recognise that every life is part of a larger whole (i.e the natural order) is to find comfort in the idea that your loved one continues to exist in the grand scheme of things - maybe not in an afterlife but definitely re-embedded into nature.

Conclusion

Grief is an inevitable part of the human experience, but applying Stoic principles, can help us navigate the difficult journey through grief with greater resilience, wisdom, and inner peace. Focusing on what we can control, embracing virtues and reflecting on the impermanence of life can provide a sense of solace and perspective. In the face of grief, Stoicism offers a framework that empowers us to transform our pain into a source of strength and growth, honoring those that we have lost by living our own life with purpose and integrity.

Mastering the Art of Habits: How to break bad habits and build good ones for productivity

Habits are an essential component to optimising productivity. As a student, much of my success was thanks to a strong foundation of habits rather than ‘academic talent’ alone. Most of my implementation of habits and ideas in this article have been adapted from James Clear’s ‘Atomic Habits’, and while I would absolutely recommend reading that book, I hope that giving personal anecdotes, analogies and examples here as a recent student and in my early career will allow you to implement the techniques more effectively into your life. The long term compounding results of consistent habits in contrast to the distracted state that we’re susceptible to in the modern world is evidence of the enormous upsides to a disciplined lifestyle built on a foundation of systems and habits.

The Formation of Habits

The Habit Loop

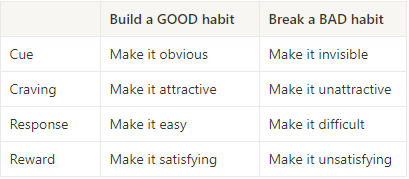

All habits both good and bad share the same four essential components: Cue, craving, response and reward which can be arranged into the habit loop. If there is sufficient amounts of each component in a behaviour that is spread over a long enough time horizon, it will turn into a habit. Understanding (and more importantly knowing how to manipulate the habit loop) is critical to allow you to build the strong good habits that are desirable as a student and break the bad undesirable ones. We can understand how to utilise the habit loop by breaking down the four components.

The cue is the activity or event that triggers the habit. It gives the signal to your brain to start a behaviour and begins predicting the reward. This sets the stage for the habit to unfold and without the cue, the habit loop cannot begin.

The craving is the motivational force behind the habit which provides the drive for you to perform the behaviour. It’s the strange feeling you get in your gut as you uncontrollably feel the pull to do a given behaviour.

The response is the performed action of the habit itself. This could be a thought, a physical action or a combination of both. This follows the craving you have to perform the action that gets you the reward.

Finally, the reward is the end goal of the habit loop that satisfies the craving and reinforces the behaviour. The reward teaches your brain whether this particular behaviour and associated habit loop is worth repeating in the future. If it is, a habit is formed.

It should now be clearer on how you can manipulate these four components to aid in building strong habits and break bad ones.

Building a Habit

With the four parts of the habit loop a little clearer, we can now investigate how to apply the principle of a habit loop. To see this in action let’s look at building a GOOD habit and breaking a BAD one.

A GOOD habit that we’ll look at is reading before bed each night. The cue here might be to place your book back on your pillow each morning after you’ve made your bed. This visual cue will help to signal to your brain each night that it’s time to read. The craving will eventually be the enjoyment, relaxation or exciting story that you get from the reading. The anticipation of these positive outcomes creates a desire to read. The response is the reading activity itself. This can be made more appealing and attractive by setting a reasonable reading target each day which can start small (such as 5 pages per day) and slowly increased over time. Finally the reward which as well as the sense of accomplishment, could be something like allowing yourself to have your favourite snack or drink while reading. This reinforces the habit which makes it more likely that it will stick.

The BAD habit we’ll look at is reducing excessive phone checking while working. The cue might be something obvious such as a notification on your phone, or something more subtle such as the creeping boredom that arises during tedious or difficult work. The craving is the desire to see the content of the notification or to take a break from the work. The response would be picking up the phone to see the notification or to scroll through Instagram or TikTok and the reward is the dopamine hit that you get each time you do this. To break this habit you could:

Turn off non-essential notifications or removing your phone from the room in which you’re studying. (cue)

Acknowledge the craving and remind yourself of the goal to stay focused. (craving)

Set a timer for focused work intervals (such as pomodoro) or use apps or tools that block distracting websites and apps during work hours. (response)

After a focused work session, take a short walk, enjoy a snack, or do a quick mindfulness exercise. (reward)

Environment Design

One important way to ensure that habits stick is reducing the mental friction between your motivation to want to do it and the behaviour itself. In Atomic Habits, James Clear outlines an extremely effective technique to do this: Environment Design which is the act of priming your environment for future use. Want to improve your grades and study more? Tidy your work area at the end of each day ready to start the next. Want to exercise more? Get your workout clothes ready the night before. Want to cook more rather than order in food? Maintain a clean kitchen environment with a fridge and pantry that has sufficient food for a range of meals. The idea is that you want to make the habit the path of least resistance, and contrary to most peoples intuition, environment design isn’t necessarily a difficult thing to maintain once you set out to do it. This principle runs on momentum.

To maintain an environment for future use requires a small amount of consistent effort. In contrast, the effort required to perform the tasks (such as studying or exercising) is far more if the environment hasn’t been primed for use. Overall, it’s likely that maintaining a ‘primed environment’ requires more energy and effort, but the impact of this effort on your ability to perform the behaviour is far less than the large effort spikes required without maintaining a useable environment. It’s far more effective to reduce friction than expend the energy required to try to overcome it.

Identity Based Habits

If you’re attempting a drastic change it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the amount of bad habits you’re trying to break and the amount of good ones you’re trying to form. Rather than having to constantly balance multiple habits at a time, it’s often much easier to embrace a new or refined identity. You may be thinking that assuming a new identity is too radical a change or unsustainable long term, but it often only requires small shifts in behaviours and mindsets to transform an identity.

Let’s look at an example. Imagine two people who are on a night out and trying to quit alcohol. These could be any type of person from university student to working professional. When offered a drink, person 1 replies with: “No thanks, I’m trying to quit alcohol”. This immediately assumes the identity of someone who drinks alcohol, but is trying to quit. Person 2 on the other hand replies with: “No thanks, I don’t drink”. This subtle difference in the responses is the key to the identity change. Person two has embodied the identity of someone who doesn’t drink rather than someone who’s trying to quit and thus is much more likely to align his actions, behaviours and ultimately habits to that new identity.

This can be applied to students, knowledge workers, entrepreneurs, people looking to improve health and fitness, learners of instruments and much more. James Clear outlines a simple two step process for this:

Decide the type of person you want to be

Prove it to yourself with small wins

When faced with a situation in which you feel pulled towards bad habits, ask yourself:

“What would a xxxx person do?”

If you’re a student struggling with studying, ask: “What would a high achieving student do?”. If you find yourself procrastinating, ask: “What would a proactive person do?”. If you’ve been eating unhealthily, ask: “What would someone healthy do?”. These simple questions can light the path towards progress.

Tracking your Progress

When building a new habit, one of the most important actions to ensure long lasting success is to track progress towards the behaviour changes. Building new habits is hard, and it’s rarely a linear path from point 1 (your current self) to point 2 (your future self with the new habit). So, having a way to track the progress is critical to maximise your chance of recovering from missed days and to see visible progress towards your goals.

Habit tracking

Habit tracking can be done in several ways and the way that you implement it will very much depend on your personal preference, your available time to track and even the types of habits that you’re tracking. At the fundamental level habit tracking comes down to one question:

“Did I do habit today? YES or NO”

With this, it helps to break down habits into specific, actionable and deliverable milestones. Rather than having a habit of reading more often, a better habit would be reading 10 pages a day. In which case, the question becomes: “Did I read 10 pages today? YES or NO”.

So what are some of the ways that you can implement habit trackers into your day? The simplest way is a simple pen and paper. Segment the week or month into each day and write your habits as columns or rows next to the days, then each day simply tick off which habits you’ve stuck to. This can be as simple as on a scrap piece of paper or (as I like to do) in a notebook for future reference.

Another option is to setup something similar on a digital platform or app. There are many apps such as Microsoft To-Do and Todoist, but my favourite digital product for this (although I prefer the analogue style of pen and paper) has been Notion. Notion has many free templates online already which you can download for habit tracking but I’ve found it much better to setup a habit tracking dashboard in the app itself.

Reflection and Review

The final piece of advice that has been most valuable for me in my journey of cultivating productive habits has been to have regular reflection and review sessions to determine how progress towards the habits is going and what needs to change. For me, this comes in the form of a habit journal - which forms part of my main journal. But, like most things here, you must find the solution that works best for you. The reflection may come as a sort of meditation exercise (if you want to make a habit of meditating then this is perfect), or it could be a discussion with an accountability buddy who’s on a habit journey themselves, or it could be a journal like I do.

Conclusion

If you’ve reached this far then it’s clear you’re serious about building better habits and I would wholly recommend reading further into this with James Clear’s Atomic Habits. The journey to self-improvement is not always easy, but with the right strategies, and a bit of patience, you can create lasting positive changes in your life. Remember, start small and be consistent. Celebrate your progress along the way and don’t be too hard on yourself when setbacks occur. By understanding the science of habits, leveraging tools like trackers, and fostering a supportive environment, you can make your goals a reality.

Stoicism for Students: How a timeless philosophy can transform our approach to studying

In recent years, it seems like there’s been a surge of interest in the ancient philosophy of stoicism. Data from Google trends shows that in just the past 5 years, there’s been a 600% increase in interest for this topic and the r/stoicism subreddit has grown from 840 to more than 610,000 members between 2012 to 2024.

The reason for this resurgence is likely more complicated than a brief analysis can uncover. Perhaps it’s the pragmatic insights that stoicism gives for leading a fulfilling and meaningful life, or the close connection between the philosophy it teaches and the habits of history’s greatest minds, or maybe it’s as a rebellion or resistance against the seemingly growing trend of abdication of personal responsibility - but that’s a topic for another article. Here we’ll explore how this philosophy of discipline and self-sacrifice can be applied to a group with a culture that stereotypically displays the least amount of similarity to stoicism: students.

What is Stoicism

Being ‘stoic’ often has a connotation of being brave or indifferent or restrained in the face of adversity. It’s the classic “Keep calm and carry on” mantra in a nutshell. And although Stoicism does encompass that resilient indifference to external circumstances, it’s core principle can be summarised as something much more fundamental. In his book ‘The Daily Stoic’, Ryan Holiday (perhaps the most well known ‘modern stoic’) explains that “Stoicism teaches that we can’t control or rely on anything outside… our ability to use reason to choose how we categorize, respond and reorient ourselves to external events”. In other words, the backbone of stoicism is the ability to react (and in many cases, not react) to external situations - a form of self discipline. So this leads to the question: why aren’t students stoic?

I must admit that this question is slightly misleading and unfair on the part of many students and I’m vastly generalising the global student population here. But from my experience of being a student, and from observing the behaviours of other students, there are some key takeaways from the teachings of Stoicism that, if applied correctly, could dramatically increase the productive output of students.

How can Stoicism benefit students

1. Managing Stress and Anxiety

“You have power over your mind - not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength.” – Marcus Aurelius

Most students at some point will be faced with a crippling amount of coursework, glooming deadlines and a seemingly impossible amount of extracurricular and social commitments to maintain. It can be all too easy to work - as Cal Newport writes in Slow Productivity - dangerously close to our breaking point. As a result, reaching that breaking point can be just an extra assignment, one poor study session or even just a marginally less productive day away and in most cases this will lead to growing stress, anxiety and eventual burnout.

However, this isn’t a dead end hopeless situation that all students must face. By following one of the core principles of stoicism - “We Don’t Control External Events, Only Our Thoughts, Opinions, Decisions and Duties” - we can forge a powerful control over the stress of student life. This isn’t to suggest that we should be passively meandering through our studies care free with the attitude that ‘whatever happens, happens’. Rather it’s a way of taking control of the situations - and more importantly - our reaction to the situations we face as students.

Got a new assignment? You have the control to get that done now. Don’t understand the contents of a lecture? You have the control to re-watch, -read or -learn the content. Upcoming exam that you’re stressing about? Again, you have the control to start studying now. By recognising that you have control over your actions and how you respond to external events, you can reduce the stress and anxiety that typically come with student life.

It’s this shift from being a victim of the responsibilities of a student to having the control to conquer the challenges that come with it, that is a fundamental aspect of stoicism that can be incredibly empowering for students. It shifts the narrative from being overwhelmed by tasks to being in charge and capable of overcoming them. This change in perspective can greatly reduce the stress that comes with the overhead worries of being a student. Stoicism teaches individuals to be content with what they have and to accept the things they cannot change. This powerful lesson can allow individuals to focus time and energy on more productive and meaningful pursuits.

2. Improving focus and productivity

"First say to yourself what you would be; and then do what you have to do." – Epictetus

It’s unlikely that the early stoics - Zeno, Seneca, Marcus Aurelius and the likes - were hyper-fixated on productivity in much the same way as modern workers and students are. But, as I’m sure you’ve experienced at some point, effective time management is vital for productivity, and Stoicism offers valuable insights on prioritising and allocating time efficiently. According to the Epictetus:

“The chief task in life is simply this: to identify and separate matters so that I can say clearly to myself which are externals not under my control, and which have to do with the choices I actually control.”

This perspective enables individuals to focus their time and energy on what they can control, reducing wasted effort on uncontrollable factors. By concentrating on what they can influence, Stoics make better decisions about time management.

Stoics like Marcus Aurelius, Epictetus and Seneca believed in doing what matters most, taught that overwhelming tasks can be broken into smaller parts and advocated for preserving time and energy where possible. And the great thing for us is that all of these ideas can be be efficiently applied to modern working life. Techniques like task prioritisation, progress milestone tracking and time blocking have been popular for increasing effective productivity but all are in some form some evolution of the basic principles taught by the stoics 2,000 years ago.

3. Handling failure and setbacks

“In all things, there is a portion of what we can and a portion of what we cannot control.” – Epictetus

Failure is something that all students will face at some point and it will come in different forms depending on the student. One student may view a grade of 68% (a 3.9 GPA in the US) as a complete failure while another would’ve worked tirelessly for the same grade. We set our own threshold of what is considered a failure. But, regardless of where this threshold is set, it would be unwise to expect not to meet failure. So, now that we expect setbacks to occur in our studies, how can stoicism aid us in dealing with them? Rocky put it best when he said “It’s not about how hard you hit, but how well you can get back up and keep moving forward”.

Failure and setbacks will occur during our time as students. More important than avoiding these setbacks, therefore, is our ability to rebound and learn from them. As previously mentioned, one of the core principles of stoicism is to take ownership of things that are within our control. So if you face a setback for whatever reason, worry not about the factors that led to it that were outside of your control, but do consider how you could’ve controlled the factors within your control better.

4. Developing Self-Discipline

“First say to yourself what you would be; and then do what you have to do.” – Epictetus

It’s no wonder that a philosophy structured around the pursuit of personal development and self-discipline directly improves both of these skills. But self-discipline isn’t just some neat skill that makes you more productive. It enables you to maintain control over your actions and reactions, leading to better focus, productivity, and stress management. Most of all, self discipline allows us to trust ourselves when we say we’re going to do something.

You see, self-discipline is a form of compounding self-trust. If you tell yourself you’re going to wake up at 7AM and do it, congratulations, you’ve just earned some discipline points and now intrinsically trust yourself to do it next time. Do this over and over and over again and you build a confidence that you can stick with what you set to do. If, on the other hand, you tell yourself you’re going to do something but let yourself down when it comes time to doing it (whether that’s because the thing itself is hard, or you’re not motivated, or you forget), then your mind starts to not trust itself in completing these tasks. As a result, there exists a significant amount of cognitive effort to get started with, and continue a given task - especially if it’s hard.

This goes back to the famous saying by former Navy SEAL Jocko Willink: "Discipline Equals Freedom." When you have self-discipline you take ownership of your actions. As a student this means taking ownership of our studying, our time and ultimately our education which leads to a more profound understanding and improved academic performance. It also cultivates resilience, allowing us to navigate challenges and setbacks more effectively. Furthermore, self-discipline can encourage healthier lifestyle choices, such as regular exercise and balanced diet, which enhances overall wellbeing and academic performance. Ultimately, developing self-discipline empowers us to lead more balanced, fulfilling, and successful lives both during their academic journey and beyond. Self-discipline is a skill, and like all skills, it must be practiced consistently to see it’s fruits.

6. Achieve a strong work-life balance

“Others have been in poor health from overindulgence and high living, before exile has provided strength, forcing them to live a more vigorous life.” – Musonius Rufus

A good work life balance is an essential component of long term productivity, success and above all happiness. It’s no wonder then that this was something that the stoics were focused on. How we actually implement techniques to improve this balance is a topic of intense debate in the world of productivity. By all accounts the stoics worked at a much more natural pace than the frenetic pace of modern life. As a student, this frantic work schedule can often be exaggerated to the nth degree with endless pre-deadline cramming. Later in this article we’ll explore some methods to combat this, but I’d once again recommend Cal Newport’s Slow Productivity for more information on working at a more natural pace.

Let’s first take the following example of a student who recently failed an exam. He may adopt the attribute this failure to the fact the contents of the course were too difficult or that he didn’t have enough time to study. Yet, he spent at most, 30 minutes a day studying and barely attended lectures due to other commitments. If the goal (which it very well might not be, but given that you’re reading this article, I assume it is) is to achieve the best grades possible in a healthy and productive manner, then certain commitments must be sacrificed. After all, if you don’t sacrifice for what you want, what you want becomes the sacrifice. I’d recommend listing out your five main commitments that are expected to be consistent over the next three to five years. Then place them in order of importance or significance. Then assign how much time per week you’re willing to sacrifice for these pursuits. This may look like:

Health & Fitness - 20hrs

Family - 7hrs

Studies - 45hrs

Friends - 10hrs

Video Games - 5hrs

Bear in mind that this shouldn’t be a concrete time commitment - studying may get more hours during exam season and less over the summer holidays. Family and friends may be the opposite. However, having some metric to plan you’re time to different commitments is a useful tricks to manage a healthy work life balance.

7. Build a strong mind and body

“Don't explain your philosophy. Embody it.” – Epictetus

As has (hopefully) been clear throughout this article, stoicism gives plenty of guidance for developing a strong mind by teaching the importance of discipline, self-mastery, and wisdom. To a student these are invaluable skills that can greatly enhance their academic performance and overall wellbeing. But stoicism also recognises the value of having a strong and healthy body. The stoics believed that a healthy body was a direct result of a healthy mind and vice versa.

Applying this to the lives of students, stoicism offers valuable insights into how students can resist the temptations and degenerate activities that often come with student life, such as excessive partying, procrastination, and unhealthy lifestyle habits. It teaches that our reactions to external events are within our control. This means that we have the power to resist temptations and degenerate activities by changing our perception of them.

For instance, rather than viewing a party as an opportunity for fun and pleasure, we can perceive it as a potential obstacle to our academic goals and personal development. Similarly, we can view procrastination not as a harmless way to avoid work, but as a hindrance to our productivity and success. By changing our perspective, we can empower ourselves to resist these temptations and make better decisions that align with our values and goals. As the stoics often taught, life is a game of balance.

Most students will at some point be faced with choices and often these choices come as a tradeoff between sacrificing long term goals for short term enjoyment. Stay in and study or go out and party? Study all day or hit the gym? Notice how none of these choices are immediately obvious as to which is most important. It is up to you to determine the correct balance of priorities and hopefully after reading this article, you can use stoicism to aid you in that quest.

How to implement stoicism as a student

Daily reflection: Taking a few minutes each day to reflect on your actions, decisions, and experiences can help you align with your stoic principles. It allows you to identify areas where you may have strayed from your values, and plan how you can better embody stoicism in the future.

Mindfulness practices: Mindfulness is a key aspect of stoicism. It involves being fully present in the moment and accepting it without judgement. You can cultivate mindfulness through practices such as meditation, mindful eating, or simply taking a few moments each day to focus solely on your breathing.

Voluntary discomfort: Stoics regularly practice voluntary discomfort to remind themselves that they can endure hardships. As a student, this might mean taking a cold shower, studying without distractions for a set time, waking up early, or resisting the pull of endless scrolling. This practice can help build resilience and refocus your priorities as discussed in the first section.

Journaling: Writing in a journal can be a form of meditation. It allows you to express your thoughts, reflect on your day, and plan for the future. Journaling can also be a tool to reinforce your stoic beliefs and remind yourself of the stoic principles you want to embody.

Practice gratitude: Practicing gratitude is a simple and effective way to shift your focus from what you lack to what you have. This aligns with the stoic principle of being content with what you have. Each day, take a moment to write down or mentally note something you are grateful for. You might be grateful for the friendships you have, the support of your family, your self-motivation or even just grateful for the ability to pursue an education.

In conclusion, Stoicism, with its core principles of self-discipline, resilience, and focusing on what one can control, offers invaluable guidance for students navigating the challenges of academic life. It provides practical strategies for managing stress, improving productivity, handling failure, developing self-discipline, achieving a work-life balance, and building a strong mind and body. More importantly, Stoicism encourages a mindset of mindful living, gratitude, and continual self-improvement. While the journey of education can often be demanding and stressful, Stoicism offers a philosophical compass to guide students towards a fulfilling and balanced academic experience. By practicing Stoic principles, students can transform their approach to studying, bolster their academic performance, and cultivate a life-long philosophy for personal growth and accomplishment.

What is Parkinson’s Law? And how to defeat it

One of the most infamous pop-culture quotes of all time comes from the Spider Man comics which states: "With great power, comes great responsibility". However, when you hear that quote, I doubt you think of how it can relate to time management skills. But I think that with slight adjustments, this quote can give some clear guidance on how to manage our time more efficiently.

Let's instead think of the quote as: "With more free time comes more responsibility". Now we can begin to gather some sort of understanding of what this principle is saying. Put simply, it states that as we are given more free time (usually experienced by those leaving school, at university or managing their own time/business), there is far more importance put on spending that time responsibly by planning and scheduling.

If you've left school, you've almost certainly experienced this. Through our early lives during school, almost all of our working time is dictated by timetables and schedules. But as we move through to college, university and the working world, we are faced with a bit of a dilemma: We have more free time, but we have to plan how we use that time to complete more tasks - often of higher complexity. This can be quite challenging.

What is Parkinson's Law

Ever thought about why students always leave assignments until the day before the deadline? Or why some have a simple task to do in a given day, yet take the whole day to complete it? There is this idea known as Parkinson's Law which states: "work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion". Briefly put, this means that if we plan on completing a task in a given time, we'll probably take the whole time to complete it. For example, if we gave ourselves a week to finish an assignment, we'd likely take the whole week to complete it. However, if we constrained this deadline to 3 days, we'd likely finish in that time constraint without compromising the quality of the work.

Even trivial tasks can fall victim to Parkinson's law, and you've almost certainly experienced it in one form or another. Whether that's as the student in the example above, or while setting deadlines for yourself. Although the deadline for the task might be weeks in the future, often times giving ourselves such a long time to complete the task can be unproductive and unhelpful.

1. Artificial deadlines

Another effective technique that can be used in conjunction with time blocking is the establishment of artificial deadlines. The concept of artificial deadlines is quite straightforward: you establish a deadline that is earlier than the actual required completion time. This strategy becomes especially beneficial in the context of projects that do not come with a strict, predetermined deadline.

For instance, in the case of writing this article, there isn't an explicit deadline set. However, in order to ensure that I complete this task efficiently, I've imposed an artificial deadline on myself. This self-imposed deadline serves as a motivator, pushing me towards completion. Without this artificial deadline, there's a chance that I might have lacked the necessary motivation to finish the task.

Employing time-blocking techniques in combination with artificial deadlines provides a robust strategy for mitigating the effects of Parkinson's Law, which states that 'work expands to fill the time available for its completion'. However, it's important to note that the most effective method for reducing the impacts of Parkinson's Law is to recognize its presence and influence in the first place. By being mindful of this phenomenon, we can take proactive steps to manage our time more efficiently.

2. Break Down Your Tasks and Deadlines

To counter Parkinson's Law, consider breaking tasks into manageable chunks, a method known as task chunking. This makes complex projects less overwhelming and more approachable by allowing focus on one piece at a time, thereby creating a sense of achievement with each completed part. Assigning a specific deadline to each task chunk enhances productivity and prompts action, helping to fend off Parkinson's Law, which dictates that work expands to fill the time available for its completion.

By setting a limit on how much time each part of the task should take, you encourage efficient use of time. However, it's important to set realistic deadlines. Overly tight deadlines can cause stress and potentially compromise work quality, while too lenient deadlines may not provide enough motivation to get started.

3. Know what ‘Done’ means

A strategy to counter Parkinson's Law is to define 'done' for each task, a vital step in time management. Often, we prolong tasks beyond completion due to unclear endpoints stemming from perfectionism, vague goals, or overwork habits. This inefficiency wastes time and resources.

Defining 'done' involves creating a specific, clear completion criterion, such as a deliverable, an outcome, or a set of criteria. This definition should be so clear that there's no ambiguity about task completion. For example, 'done' for a report might be writing all sections and proofreading, while for a project, it could be achieving goals and delivering expected outcomes.

Having a clear 'done' definition allows you to focus on the task, prevent unnecessary work, and increase efficiency. The aim is not to work harder but smarter, aiding in countering Parkinson's Law.

4. Time-blocking

When I allot an entire day to write an article, complete an assignment, or delve into a specific subject matter, I often find that I end up using the entirety of the day to accomplish that singular task. This, however, changes when I have pre-planned engagements like a sports activity or a social outing with friends that take up around three hours of my day. Despite the time constraint, I still manage to complete the task at hand without compromising the quality, all within the reduced timeframe.

The secret behind my efficiency is a time management technique known as time-blocking. Time-blocking is a method where we dedicate specific blocks of time in our daily schedule to focus exclusively on one task. During these blocked-off periods, our attention is solely on the task at hand, with no room for distractions. This could involve blocking off two or three hours to wrap up an assignment, work on a project, or any other task that requires undivided attention. The crucial aspect is that the blocked time is reserved exclusively for the task we have assigned to it.

While time-blocking can significantly boost productivity, using it for every task may lead to the contrary. Overuse of time-blocking may lead to exhaustion and decreased productivity due to the intense focus required for each block. Hence, I suggest that time-blocking should be judiciously used for one or two of the primary tasks that need to be accomplished in a day. This way, it aids in maintaining productivity and focus, without causing burnout.

5. Have a reason to finish early

The reason why Parkinson's Law is so prevalent in university and business is because there often aren't enough incentives to complete tasks early. You may have even experienced this yourself. "Already finished your tasks? Here's additional work." or "You finished quickly! We’re shortening the next deadline."

Even leaders can find it tempting to refine a current task instead of starting a new one. This can serve as a safety net, helping to avoid the next, potentially intimidating task. The unknown can be daunting, but it's crucial to set a good example for your team. When you're done, finish early.

To counteract this, establish incentives for completing each phase of your work. Reward yourself for finishing early, whether it's by taking a short break, browsing the web, or going for a walk. Do something you enjoy and relish the satisfaction of earning it. The key is to connect rewards to results, not time spent. Make your goals specific and outcome-oriented – strive to 'complete this project' instead of 'spending an hour' on it without finishing.