ARTICLES

The 7 habits of highly productive students

Academic success is not just about intelligence or natural talent. It’s also about playing the game of ‘school’ or ‘university’ most effectively. Highly successful students often excel not because they are inherently smarter, but because they have developed a set of habits that enhance their learning, productivity, and overall performance. And the great thing about them is that these habits can be learned and adopted by anyone willing to put in the effort.

As well as studying for my degrees, I spent my time at university exploring the habits of the most successful students past and present to try to understand what makes them stand out from the crowd. In this article, we will explore the seven key habits that set highly effective students apart. Whether you're in high school, college, or pursuing advanced degrees, integrating these habits into your routine can transform your educational experience and pave the way for lifelong success.

1. Don’t fall behind

If there’s one habit that you take away from this article, it should be this: Don’t fall behind. While university affords students more freedom over how time is spent than school, it’s worth avoiding the mistake of being complacent in your studies. At the start of a new semester, it can seem like assignments, exams and deadlines are far away, but given that there’s often only a matter of weeks between the start of a new semester and the first graded assignments, falling behind is far from ideal.

To get a better understanding of why falling behind is suboptimal (beyond the simple common sense reasoning), consider two students in the first weeks of a semester. Student 1 keeps up with the lecture content and on top of any class exercises, while Student 2 postpones it. By week 3, when assignments begin, Student 1 can focus on producing high-quality work with ease, whereas Student 2 must catch up on missed content while also completing the assignment, leading to increased stress and lower quality work.

Student 1 and student 2 will have effectively spent the same amount of time working over the three weeks, but student 1 spread this time more evenly, leading to a less stressful time working on the assignment with more time to check over his work and polish the submission.

This is an example of a gain-loss asymmetry. In other words, falling behind means that you actually have to do more work to catch back up than if you were to stay on top of the work or better yet, get ahead.

2. Use your free time wisely

As mentioned in habit 1, university life offers students a huge amount of free time if spent correctly. It’s unlikely that during school studies, you’ll have had as much free time (or at least as much freedom over your time) as you do at university. And it’s crucial that you spend this free time productively. But productively, here, doesn’t necessarily mean studying or working. There’s far more to your time at university than studying and spending time productively doesn’t always mean doing more work.

In Cal Newport’s “Slow Productivity”, he notes that one of the principles of Slow Productivity (a system that allows us to avoid the frenetic work culture of modern life) is to work at a natural pace. This means that time spent away from your work can actually aid your productivity when you pick it back up again.

What are some of the ways you can spend your free time wisely? There’s an almost infinite list of ways - each depending on your interests and current commitments. Perhaps it’s spending time with friends socialising, or working out in the gym, or exploring side projects or starting a business. There’s a huge variety of ways to spend free time wisely that gives you a break from studying. Just be cautious to maintain a healthy balance of work and play.

3. Embrace ignorance. Avoid arrogance

Starting at college or university can sometimes feel like a competition where the prize are your grades and the competitors are your fellow classmates. And to some degree it is. Although as I point out in some of my other articles, the idea about classmates being ‘competition’ is a poor mindset to have. Instead it’s better to utilise collaboration to foster friendships, collectively improve understanding and to aid in your quest to compete against your real competition - your former self. But let’s assume that you think as many do: That you’re in a academic battle against your cohort. In order to try and get one stage ahead of the competition, it can be tempting to try to enter university with the arrogant attitude that you know more about the content that will be taught to you than your classmates.

However, this mindset can be massively detrimental to your learning experience. Entering with a sense of overconfidence can close you off to new perspectives and valuable insights that are crucial for a deep understanding of whatever it is that you’re learning. Let’s look at why this is by considering two students: Student one enters university having shallowly consumed a broad range of content on his degree subject. Student two enters university with less specialist knowledge of the subject but with a more open minded approach to learning. This is how their academic development and total understanding of the subject may look like:

While student 1 starts with more knowledge than student 2, an arrogant and more closed minded mindset to learning means that over time, student 2 absorbs much more knowledge than student 1 and surpasses his understanding of the subject. In an ideal world you want both traits. Enter university with an open mindset, ask questions, and seek help when needed. But also engage your curiosity by learning about the subject before hand and get ahead of the crowd (as we’ll see with the next habit).

4. Be proactive

On the flip side of the coin to how you spend your free time is how you spend your time that you dedicate to work. Most of this time should be dedicated to the most obvious and important tasks: Completing assignments, attending lectures, studying for exams and preparing for seminars. But a small amount of this work time (perhaps 5-10%) should be spent on ‘proactive activities’ that separate you from the general student. It’s often how this 5% of time is spent that will determine who the high achievers are, and who the average students are.

The great thing about proactive activities is that they often have a much larger return on effort and time than grinding through tedious studying activities. To see why this is, let’s take a look at an example. Imagine that you’re about to enter exam season, and have found yourself struggling with one of the concepts from the previous semester. One approach to dealing with this would be to grind out the study sessions which will likely work but typically requires several hours of tedious and often stressful work to try and connect together concepts and ideas to form an understanding.

Instead, an alternative approach which is much more proactive would be to make use of the office hours of the lecturer whose content it is that you’re struggling with. Given that most students don’t take advantage of these sessions, you’ll often find yourself in one-to-one sessions with a lecturer and are given much more tailored tutoring on topics of your choosing.

Other proactive activities might include pre-reading lecture content before the lecture which allows you to follow the more nuanced ideas that may be discussed in the lecture. You may also find external reading on resources and topics surrounding the content of lectures beneficial in providing you with a much deeper and more intuitive understanding of the content. This often means that in an exam situation, the answers to the questions will come much more naturally rather than having to resort to pre-thought answers. A final suggestion would be to get ahead before or early into each semester in planning assignments and upcoming deadlines for the forthcoming semester.

The common feature of all of these suggestions is that they are based on taking initiative to get ahead of the game early on. Proactivity can often outweigh the importance of productivity if implemented effectively.

5. Build strong systems

One thing that became apparent to me during my time at university is that strong, reliable systems can make the university experience so much easier and more pleasant. If you set up reliable systems that you can trust for studying, assignments, exercise, or even the simplest things like waking up or going to sleep on time, you greatly reduce the amount of conscious action that’s required to perform these actions. And this is actually a well documented phenomenon in productivity and is explored in James Clear’s Atomic Habits. To truly build a strong foundation of habits and systems, I’d recommend reading the book, but one relevant takeaway relevant to this point comes from the habit loop. Put simply, all habits can be broken down into four stages: Cue, craving, response and reward with each stage feeding into the next. In order for a habit to form, there must be a sufficient amount of incentive or drive for each of these stages.

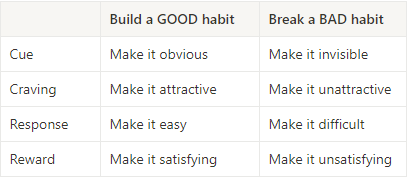

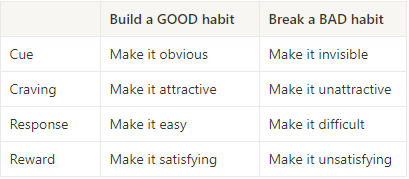

Given that both productive and unproductive habit systems are built on a foundation of habits, you can manipulate the habit loop to get your desired outcome - more good habits and less bad ones. How do you do this? By following the four laws of behaviour change:

For a comprehensive example of how to apply and optimise the habit loop as a student, take a look at my article on this here.

6. Exercise the body as much as the mind

Picture what you’d consider to be a productive, high achieving student. I’d wager that you envisioned some variation of someone at their desk or at the library studying for hours on end, day after day. While the dedication, discipline and focus displayed by this hypothetical student are all traits that high performance students share, those who have a healthy and productive lifestyle also put an equal (if not higher) priority into time spent of their physical and mental health as they do on the time spent studying. This doesn’t mean that more time should be spent exercising than studying - that would be unhealthy and unsustainable - but rather, the importance of both are equal.

A study of more than 3,500 workers in a range of industries in Denmark who were tasked with just 1 hour of weekly supervised exercise found that as muscle strength improved and body mass index decreased, there was a measurable increase in productivity [1]. Several other studies have also shown similar benefits from regular exercise on both physical health and productive output.

Implementing exercise into your routine as a student shouldn’t be too difficult. A simple 45 minute to 1 hour session three times a week is more than sufficient to ensure that you’re gaining ample benefits from the exercise.

7. Study deeply

As a student, the phrase time is money could more accurately be rephrased to time is grades. And there are two ways that I’ve found this time can be spent: With short bursts of highly intense work or as a slow burning, moderate intensity work style that is more consistent over time. The work style that you choose will depend on a number of factors including how much time you have, what content you’re studying and what type of learner you are. But whichever style of work you prefer, studying ‘deeply’ can dramatically increase the volume of work you complete.

In Cal Newport’s aptly titled ‘Deep Work’, he defines deep work as ‘activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit’. It’s not difficult to see the value of deep work - in a world of increasing distraction and stimulation (particularly among students), it’s those who are able to deeply work on a skill, task or project that are able to generate the highest chance of success.

To implement ‘deep study’ into your life, you could utilise a whole range of techniques. One method that has been particularly beneficial to me has been to embrace boredom. We live in a world in which at any moment, you can get immediate mental stimulation from apps like Instagram or TikTok. As such, for the first time in history, our ability to be bored has become an estranged skill. So what happens when you get bored when working or certain study sessions become difficult? You’ll immediately get the craving (as mentioned in 5) to get mental stimulation which today, typically means that you’ll reach for your phone. This is not a particularly desirable situation since boredom is an important skill for improving focus. So in future, avoid constantly seeking stimulation such as checking your phone during every spare moment and embrace the boredom that naturally comes with studying.

There are several other ways to embrace a deep work style to your studies such as being strict with your time management, setting dedicated times during the day for social media use, cultivating a study environment that is void from distractions and setting up strong routines and rituals around your studying. All of these lead to the same result: A style of studying that embraces the flow state of highly efficient and productive work that will not only benefit you in your studies but will be a valuable skill as you enter the workforce.

Conclusion

To conclude, we’ve seen that academic success is not necessarily a matter of inherent intelligence or natural talent alone. But rather, it comes as a result of strong habits and skills that give us the best chances of maximising our academic potential. The seven habits discussed—staying ahead in your studies, using free time wisely, being proactive, embracing ignorance and avoiding arrogance, building strong systems, balancing physical and mental health, and studying deeply—are powerful tools that can significantly enhance your learning, productivity, and overall performance. By integrating these habits into your daily routine, you can transform your educational experience, reduce stress, and pave the way for lifelong success.

Mastering the Art of Habits: How to break bad habits and build good ones for productivity

Habits are an essential component to optimising productivity. As a student, much of my success was thanks to a strong foundation of habits rather than ‘academic talent’ alone. Most of my implementation of habits and ideas in this article have been adapted from James Clear’s ‘Atomic Habits’, and while I would absolutely recommend reading that book, I hope that giving personal anecdotes, analogies and examples here as a recent student and in my early career will allow you to implement the techniques more effectively into your life. The long term compounding results of consistent habits in contrast to the distracted state that we’re susceptible to in the modern world is evidence of the enormous upsides to a disciplined lifestyle built on a foundation of systems and habits.

The Formation of Habits

The Habit Loop

All habits both good and bad share the same four essential components: Cue, craving, response and reward which can be arranged into the habit loop. If there is sufficient amounts of each component in a behaviour that is spread over a long enough time horizon, it will turn into a habit. Understanding (and more importantly knowing how to manipulate the habit loop) is critical to allow you to build the strong good habits that are desirable as a student and break the bad undesirable ones. We can understand how to utilise the habit loop by breaking down the four components.

The cue is the activity or event that triggers the habit. It gives the signal to your brain to start a behaviour and begins predicting the reward. This sets the stage for the habit to unfold and without the cue, the habit loop cannot begin.

The craving is the motivational force behind the habit which provides the drive for you to perform the behaviour. It’s the strange feeling you get in your gut as you uncontrollably feel the pull to do a given behaviour.

The response is the performed action of the habit itself. This could be a thought, a physical action or a combination of both. This follows the craving you have to perform the action that gets you the reward.

Finally, the reward is the end goal of the habit loop that satisfies the craving and reinforces the behaviour. The reward teaches your brain whether this particular behaviour and associated habit loop is worth repeating in the future. If it is, a habit is formed.

It should now be clearer on how you can manipulate these four components to aid in building strong habits and break bad ones.

Building a Habit

With the four parts of the habit loop a little clearer, we can now investigate how to apply the principle of a habit loop. To see this in action let’s look at building a GOOD habit and breaking a BAD one.

A GOOD habit that we’ll look at is reading before bed each night. The cue here might be to place your book back on your pillow each morning after you’ve made your bed. This visual cue will help to signal to your brain each night that it’s time to read. The craving will eventually be the enjoyment, relaxation or exciting story that you get from the reading. The anticipation of these positive outcomes creates a desire to read. The response is the reading activity itself. This can be made more appealing and attractive by setting a reasonable reading target each day which can start small (such as 5 pages per day) and slowly increased over time. Finally the reward which as well as the sense of accomplishment, could be something like allowing yourself to have your favourite snack or drink while reading. This reinforces the habit which makes it more likely that it will stick.

The BAD habit we’ll look at is reducing excessive phone checking while working. The cue might be something obvious such as a notification on your phone, or something more subtle such as the creeping boredom that arises during tedious or difficult work. The craving is the desire to see the content of the notification or to take a break from the work. The response would be picking up the phone to see the notification or to scroll through Instagram or TikTok and the reward is the dopamine hit that you get each time you do this. To break this habit you could:

Turn off non-essential notifications or removing your phone from the room in which you’re studying. (cue)

Acknowledge the craving and remind yourself of the goal to stay focused. (craving)

Set a timer for focused work intervals (such as pomodoro) or use apps or tools that block distracting websites and apps during work hours. (response)

After a focused work session, take a short walk, enjoy a snack, or do a quick mindfulness exercise. (reward)

Environment Design

One important way to ensure that habits stick is reducing the mental friction between your motivation to want to do it and the behaviour itself. In Atomic Habits, James Clear outlines an extremely effective technique to do this: Environment Design which is the act of priming your environment for future use. Want to improve your grades and study more? Tidy your work area at the end of each day ready to start the next. Want to exercise more? Get your workout clothes ready the night before. Want to cook more rather than order in food? Maintain a clean kitchen environment with a fridge and pantry that has sufficient food for a range of meals. The idea is that you want to make the habit the path of least resistance, and contrary to most peoples intuition, environment design isn’t necessarily a difficult thing to maintain once you set out to do it. This principle runs on momentum.

To maintain an environment for future use requires a small amount of consistent effort. In contrast, the effort required to perform the tasks (such as studying or exercising) is far more if the environment hasn’t been primed for use. Overall, it’s likely that maintaining a ‘primed environment’ requires more energy and effort, but the impact of this effort on your ability to perform the behaviour is far less than the large effort spikes required without maintaining a useable environment. It’s far more effective to reduce friction than expend the energy required to try to overcome it.

Identity Based Habits

If you’re attempting a drastic change it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the amount of bad habits you’re trying to break and the amount of good ones you’re trying to form. Rather than having to constantly balance multiple habits at a time, it’s often much easier to embrace a new or refined identity. You may be thinking that assuming a new identity is too radical a change or unsustainable long term, but it often only requires small shifts in behaviours and mindsets to transform an identity.

Let’s look at an example. Imagine two people who are on a night out and trying to quit alcohol. These could be any type of person from university student to working professional. When offered a drink, person 1 replies with: “No thanks, I’m trying to quit alcohol”. This immediately assumes the identity of someone who drinks alcohol, but is trying to quit. Person 2 on the other hand replies with: “No thanks, I don’t drink”. This subtle difference in the responses is the key to the identity change. Person two has embodied the identity of someone who doesn’t drink rather than someone who’s trying to quit and thus is much more likely to align his actions, behaviours and ultimately habits to that new identity.

This can be applied to students, knowledge workers, entrepreneurs, people looking to improve health and fitness, learners of instruments and much more. James Clear outlines a simple two step process for this:

Decide the type of person you want to be

Prove it to yourself with small wins

When faced with a situation in which you feel pulled towards bad habits, ask yourself:

“What would a xxxx person do?”

If you’re a student struggling with studying, ask: “What would a high achieving student do?”. If you find yourself procrastinating, ask: “What would a proactive person do?”. If you’ve been eating unhealthily, ask: “What would someone healthy do?”. These simple questions can light the path towards progress.

Tracking your Progress

When building a new habit, one of the most important actions to ensure long lasting success is to track progress towards the behaviour changes. Building new habits is hard, and it’s rarely a linear path from point 1 (your current self) to point 2 (your future self with the new habit). So, having a way to track the progress is critical to maximise your chance of recovering from missed days and to see visible progress towards your goals.

Habit tracking

Habit tracking can be done in several ways and the way that you implement it will very much depend on your personal preference, your available time to track and even the types of habits that you’re tracking. At the fundamental level habit tracking comes down to one question:

“Did I do habit today? YES or NO”

With this, it helps to break down habits into specific, actionable and deliverable milestones. Rather than having a habit of reading more often, a better habit would be reading 10 pages a day. In which case, the question becomes: “Did I read 10 pages today? YES or NO”.

So what are some of the ways that you can implement habit trackers into your day? The simplest way is a simple pen and paper. Segment the week or month into each day and write your habits as columns or rows next to the days, then each day simply tick off which habits you’ve stuck to. This can be as simple as on a scrap piece of paper or (as I like to do) in a notebook for future reference.

Another option is to setup something similar on a digital platform or app. There are many apps such as Microsoft To-Do and Todoist, but my favourite digital product for this (although I prefer the analogue style of pen and paper) has been Notion. Notion has many free templates online already which you can download for habit tracking but I’ve found it much better to setup a habit tracking dashboard in the app itself.

Reflection and Review

The final piece of advice that has been most valuable for me in my journey of cultivating productive habits has been to have regular reflection and review sessions to determine how progress towards the habits is going and what needs to change. For me, this comes in the form of a habit journal - which forms part of my main journal. But, like most things here, you must find the solution that works best for you. The reflection may come as a sort of meditation exercise (if you want to make a habit of meditating then this is perfect), or it could be a discussion with an accountability buddy who’s on a habit journey themselves, or it could be a journal like I do.

Conclusion

If you’ve reached this far then it’s clear you’re serious about building better habits and I would wholly recommend reading further into this with James Clear’s Atomic Habits. The journey to self-improvement is not always easy, but with the right strategies, and a bit of patience, you can create lasting positive changes in your life. Remember, start small and be consistent. Celebrate your progress along the way and don’t be too hard on yourself when setbacks occur. By understanding the science of habits, leveraging tools like trackers, and fostering a supportive environment, you can make your goals a reality.