ARTICLES

Mastering the Art of Habits: How to break bad habits and build good ones for productivity

Habits are an essential component to optimising productivity. As a student, much of my success was thanks to a strong foundation of habits rather than ‘academic talent’ alone. Most of my implementation of habits and ideas in this article have been adapted from James Clear’s ‘Atomic Habits’, and while I would absolutely recommend reading that book, I hope that giving personal anecdotes, analogies and examples here as a recent student and in my early career will allow you to implement the techniques more effectively into your life. The long term compounding results of consistent habits in contrast to the distracted state that we’re susceptible to in the modern world is evidence of the enormous upsides to a disciplined lifestyle built on a foundation of systems and habits.

The Formation of Habits

The Habit Loop

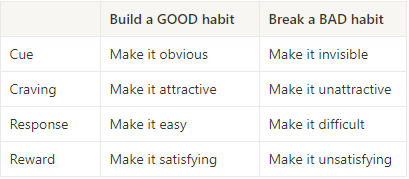

All habits both good and bad share the same four essential components: Cue, craving, response and reward which can be arranged into the habit loop. If there is sufficient amounts of each component in a behaviour that is spread over a long enough time horizon, it will turn into a habit. Understanding (and more importantly knowing how to manipulate the habit loop) is critical to allow you to build the strong good habits that are desirable as a student and break the bad undesirable ones. We can understand how to utilise the habit loop by breaking down the four components.

The cue is the activity or event that triggers the habit. It gives the signal to your brain to start a behaviour and begins predicting the reward. This sets the stage for the habit to unfold and without the cue, the habit loop cannot begin.

The craving is the motivational force behind the habit which provides the drive for you to perform the behaviour. It’s the strange feeling you get in your gut as you uncontrollably feel the pull to do a given behaviour.

The response is the performed action of the habit itself. This could be a thought, a physical action or a combination of both. This follows the craving you have to perform the action that gets you the reward.

Finally, the reward is the end goal of the habit loop that satisfies the craving and reinforces the behaviour. The reward teaches your brain whether this particular behaviour and associated habit loop is worth repeating in the future. If it is, a habit is formed.

It should now be clearer on how you can manipulate these four components to aid in building strong habits and break bad ones.

Building a Habit

With the four parts of the habit loop a little clearer, we can now investigate how to apply the principle of a habit loop. To see this in action let’s look at building a GOOD habit and breaking a BAD one.

A GOOD habit that we’ll look at is reading before bed each night. The cue here might be to place your book back on your pillow each morning after you’ve made your bed. This visual cue will help to signal to your brain each night that it’s time to read. The craving will eventually be the enjoyment, relaxation or exciting story that you get from the reading. The anticipation of these positive outcomes creates a desire to read. The response is the reading activity itself. This can be made more appealing and attractive by setting a reasonable reading target each day which can start small (such as 5 pages per day) and slowly increased over time. Finally the reward which as well as the sense of accomplishment, could be something like allowing yourself to have your favourite snack or drink while reading. This reinforces the habit which makes it more likely that it will stick.

The BAD habit we’ll look at is reducing excessive phone checking while working. The cue might be something obvious such as a notification on your phone, or something more subtle such as the creeping boredom that arises during tedious or difficult work. The craving is the desire to see the content of the notification or to take a break from the work. The response would be picking up the phone to see the notification or to scroll through Instagram or TikTok and the reward is the dopamine hit that you get each time you do this. To break this habit you could:

Turn off non-essential notifications or removing your phone from the room in which you’re studying. (cue)

Acknowledge the craving and remind yourself of the goal to stay focused. (craving)

Set a timer for focused work intervals (such as pomodoro) or use apps or tools that block distracting websites and apps during work hours. (response)

After a focused work session, take a short walk, enjoy a snack, or do a quick mindfulness exercise. (reward)

Environment Design

One important way to ensure that habits stick is reducing the mental friction between your motivation to want to do it and the behaviour itself. In Atomic Habits, James Clear outlines an extremely effective technique to do this: Environment Design which is the act of priming your environment for future use. Want to improve your grades and study more? Tidy your work area at the end of each day ready to start the next. Want to exercise more? Get your workout clothes ready the night before. Want to cook more rather than order in food? Maintain a clean kitchen environment with a fridge and pantry that has sufficient food for a range of meals. The idea is that you want to make the habit the path of least resistance, and contrary to most peoples intuition, environment design isn’t necessarily a difficult thing to maintain once you set out to do it. This principle runs on momentum.

To maintain an environment for future use requires a small amount of consistent effort. In contrast, the effort required to perform the tasks (such as studying or exercising) is far more if the environment hasn’t been primed for use. Overall, it’s likely that maintaining a ‘primed environment’ requires more energy and effort, but the impact of this effort on your ability to perform the behaviour is far less than the large effort spikes required without maintaining a useable environment. It’s far more effective to reduce friction than expend the energy required to try to overcome it.

Identity Based Habits

If you’re attempting a drastic change it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the amount of bad habits you’re trying to break and the amount of good ones you’re trying to form. Rather than having to constantly balance multiple habits at a time, it’s often much easier to embrace a new or refined identity. You may be thinking that assuming a new identity is too radical a change or unsustainable long term, but it often only requires small shifts in behaviours and mindsets to transform an identity.

Let’s look at an example. Imagine two people who are on a night out and trying to quit alcohol. These could be any type of person from university student to working professional. When offered a drink, person 1 replies with: “No thanks, I’m trying to quit alcohol”. This immediately assumes the identity of someone who drinks alcohol, but is trying to quit. Person 2 on the other hand replies with: “No thanks, I don’t drink”. This subtle difference in the responses is the key to the identity change. Person two has embodied the identity of someone who doesn’t drink rather than someone who’s trying to quit and thus is much more likely to align his actions, behaviours and ultimately habits to that new identity.

This can be applied to students, knowledge workers, entrepreneurs, people looking to improve health and fitness, learners of instruments and much more. James Clear outlines a simple two step process for this:

Decide the type of person you want to be

Prove it to yourself with small wins

When faced with a situation in which you feel pulled towards bad habits, ask yourself:

“What would a xxxx person do?”

If you’re a student struggling with studying, ask: “What would a high achieving student do?”. If you find yourself procrastinating, ask: “What would a proactive person do?”. If you’ve been eating unhealthily, ask: “What would someone healthy do?”. These simple questions can light the path towards progress.

Tracking your Progress

When building a new habit, one of the most important actions to ensure long lasting success is to track progress towards the behaviour changes. Building new habits is hard, and it’s rarely a linear path from point 1 (your current self) to point 2 (your future self with the new habit). So, having a way to track the progress is critical to maximise your chance of recovering from missed days and to see visible progress towards your goals.

Habit tracking

Habit tracking can be done in several ways and the way that you implement it will very much depend on your personal preference, your available time to track and even the types of habits that you’re tracking. At the fundamental level habit tracking comes down to one question:

“Did I do habit today? YES or NO”

With this, it helps to break down habits into specific, actionable and deliverable milestones. Rather than having a habit of reading more often, a better habit would be reading 10 pages a day. In which case, the question becomes: “Did I read 10 pages today? YES or NO”.

So what are some of the ways that you can implement habit trackers into your day? The simplest way is a simple pen and paper. Segment the week or month into each day and write your habits as columns or rows next to the days, then each day simply tick off which habits you’ve stuck to. This can be as simple as on a scrap piece of paper or (as I like to do) in a notebook for future reference.

Another option is to setup something similar on a digital platform or app. There are many apps such as Microsoft To-Do and Todoist, but my favourite digital product for this (although I prefer the analogue style of pen and paper) has been Notion. Notion has many free templates online already which you can download for habit tracking but I’ve found it much better to setup a habit tracking dashboard in the app itself.

Reflection and Review

The final piece of advice that has been most valuable for me in my journey of cultivating productive habits has been to have regular reflection and review sessions to determine how progress towards the habits is going and what needs to change. For me, this comes in the form of a habit journal - which forms part of my main journal. But, like most things here, you must find the solution that works best for you. The reflection may come as a sort of meditation exercise (if you want to make a habit of meditating then this is perfect), or it could be a discussion with an accountability buddy who’s on a habit journey themselves, or it could be a journal like I do.

Conclusion

If you’ve reached this far then it’s clear you’re serious about building better habits and I would wholly recommend reading further into this with James Clear’s Atomic Habits. The journey to self-improvement is not always easy, but with the right strategies, and a bit of patience, you can create lasting positive changes in your life. Remember, start small and be consistent. Celebrate your progress along the way and don’t be too hard on yourself when setbacks occur. By understanding the science of habits, leveraging tools like trackers, and fostering a supportive environment, you can make your goals a reality.

Designing the ideal productivity workflow: Don’t push it

Anyone who has long been on the pursuit of improving productivity likely will have been faced at some point in that journey with a crippling overload of projects, tasks and deadlines. In these situations, it’s not unlikely to be faced with a growing pile of tasks to progress with a given project and a seemingly shrinking amount of free time to work on them. This is obviously an unsustainable workflow for tackling project. Why then do so many of us fall into this style of work? And more importantly, how do we get ourselves out of it?

I had long been struggling with this problem with projects in all aspects of professional and academic life. As a student, a build up of assignments on an already heaped pile of studying required a frenetic and frantic workstyle which led to frequent burnouts and lack of motivation. Similarly, as a spacecraft engineer, time-sensitive projects comprised of highly complex tasks - often given at short notice - means that additional responsibilities for contributions to different projects grow while available time to manage the overhead admin shrinks. And also, while writing this blog and producing YouTube videos, I would have a load of half written posts and scripts, unedited footage and a seemingly endless amount of content ideas.

So what do all of these have in common? They all operate on a “Push” based workflow. This concept was first introduced to me recently while I was reading “Slow Productivity” by Cal Newport and suddenly it all clicked. The way to prevent the overload that we are all so susceptible to requires a shift from a “Push” to a “Pull” workflow.

The Problem with Pushing

Before going into the upsides of switching project workflows to a pull system, it might be helpful to define what we mean we say push or pull workflows. To understand these two workflows, we need to imagine a project - that is a collection of tasks that collectively will take several days to complete at least.

A push system works by pushing work at each stage onward to the next stage as soon as it’s been complete. In this type of system, the focus of each stage of a project is to complete the tasks and immediately hand it to the next stage in the workflow. This often leads to a linear progression where the goal is to keep work flowing steadily from start to finish. However, there are several potential downsides to this approach. For instance, if any stage of the project experiences a delay or bottleneck, the subsequent stages might either be forced to wait or, conversely, be overwhelmed with tasks once the bottleneck clears. This system often results in a build up of tasks, leading to potential overwhelm and burnout.

A pull system works by pulling in new work at a given stage only when it’s ready for it. In other words, tasks are only moved forward when there is capacity to handle them. The pull system is designed to match the pace of the project workflow, allowing a balancing of workload and preventing bottlenecks. An important point to note before continuing is that ‘projects’ refer to work that would substantial enough that it will likely take multiple sessions to complete and are often made up of several tasks.

Push Productivity by Pulling

Now that we’ve had a glimpse at the likely risks of a push based system (overload and burnout) and the key intrinsic benefit of a pull system (the aversion of backlogs), let’s look deeper at what it means to have a pull based system, how to implement it, and how to ensure it’s long term success.

Implementing a pull based system is much more than a simple system to increase productivity. It’s a way of claiming responsibility

It fundamentally shifts the attitude we have towards towards greater efficiency, responsibility, and most importantly accountability of our time and energy. This approach can lead to more thoughtful, high-quality work as you regain the time and space needed to effectively engage more deeply with your tasks.

An effective strategy is needed to implement a pull system that ensures that it effectively aids our management of projects. To do this we must have three key sections of our strategy: Implementing, managing and maintaining the pull system.

Implementing a pull system

The key feature of an effective pull workflow is a system to manage projects that avoids the risk of working on too many projects at one time. In Slow Productivity, Cal Newport suggests that we should limit the amount of work that we’re currently working on to at most three projects. There are several techniques to do that, however the one suggested by Newport and the one that I’ve found to be most beneficial is to track all projects that you’re currently commited to into two lists:

Holding Tank - The list where most projects are held until they are being currently worked on.

Active List - The list that contains the 2-3 projects that you are currently working on.

The projects that you are currently working on or which are most time critical should be added to the Active List. This list should be limited to at most 3 tasks to minimise the burden of an overload of project commitments. When you commit to new projects, first add them to the Holding Tank and when a space opens on the Active List (whether that is because the active project has been completed or become irrelevant), a project can be transferred from the Holding Tank to the Active List.

There is no limit to the amount of projects that can be held in the holding tank. But when scheduling your time, your focus should be directed most towards the Active List. It may also be worth splitting up larger projects into sub-projects. For example, instead of “Make a video on slowing down productivity” it may be split into a project for scripting the video, filming the video and editing the video.

You may be asking: “What’s the best way of planning the pull system?”. There’s no real answer here. You could set up the Holding Tank and Active List on a scrap piece of paper, in a notebook or on a digital app that can sync across devices. I like to use Notion for this for it’s advanced database handling tools. You can download my Notion Pull System Template for free here.

Managing a pull system

While a large part of the upfront work of implementing a pull system is the setup, it’s just as important to ensure that you’re managing that system effectively. In a pull system, it may come as no surprise but it’s the intake procedure that you ‘pull’ from that is critical. This can be done in two ways, depending on where the projects are coming from.

If you’re self-employed, self-studying, a freelancer or working on a side project (like this blog), it will likely be you that is the primary source of new projects on your plate. Of course, this isn’t a hard and fast rule, but in these situations, you will typically have much more control over the amount of work that is funnelled towards you: You decide what topics you’re studying, what freelance work you’re taking on, or what blog posts you’re planning on writing. While this may appear as an ideal situation for implementing a pull system (since you’re just ‘pulling’ from yourself rather than another team), it requires a certain level of discipline to work correctly.

In this case, the key is honesty with yourself regarding how many projects you take on and when. It relates to the infamous saying:

“We overestimate what we can achieve in a day and underestimate what we can achieve in a year.”

The other scenario would be in a more traditional environment of employment or education, where you may not have complete autonomy or control over the projects that you’re committed to. In this case, you may be working in an environment that hasn’t implemented a pull system and so projects may often be pushed onto you.

The key in this situation is transparency. Be clear with those who are pushing new work onto you with your current project commitments as well as give an estimate for the length of time the new project will take. It’s crucial here to build trust with those pushing the work onto you. Be transparent with your workload and capacity to take on new work and always deliver on the promises that you give to others - even if the terms of the promise have to be changed slightly.

Maintaining a pull system

The final consideration when implementing a pull system is how it will be maintained. Earlier in this blog I mentioned that there is no upper limit to the size of the Holding Tank, and while this is true, it is worth regularly purging and updating your lists once a week.

Remove any completed projects from the Active List, and replace them with projects from the Holding Tank. Delete any redundant tasks from the Holding Tank that are no longer needed and review any upcoming deadlines for all projects in both lists. Projects that are due soon should be prioritised and so it’s also worth replacing any non-urgent projects from the Active List with those in the Holding Tank that have looming deadlines.

Conclusion

In this blog post, I’ve introduced a method from minimising burnout and overload of tasks from Cal Newport’s ‘Slow Productivity’. This method is built on the principle of a ‘pull’ based workflow in which tasks are pulled from one stage of a project to the next only when there is capacity to do so. A useful way of implementing this is with a Holding Tank and Active List to manage projects in which only the three most crucial projects are worked on at any one time. If implemented correctly, the pull method can drastically increase productive output while minimising the risk of overworking, mismanagement of tasks and burnout.